First of all, I’m not a notation snob and I’m definitely not anti-tab. Without guitar tab, myself and tens of thousands of other players would probably never have stuck with the instrument long enough to get anywhere, so I’m very grateful it exists.

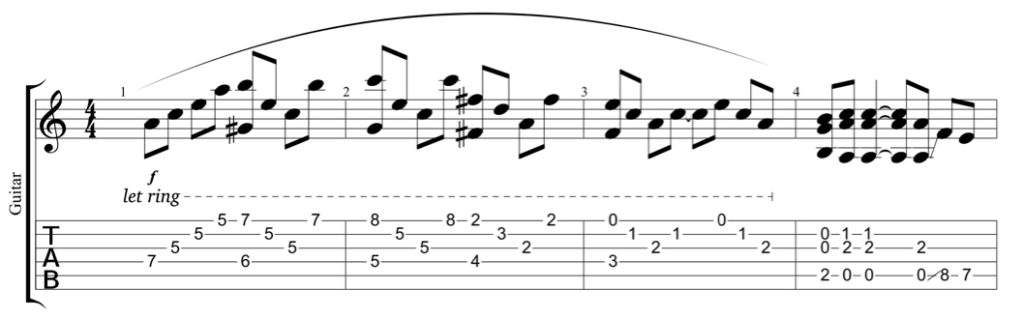

Tablature – known as tab for short – is a system for writing down music using numbers to display what to play, instead of the traditional musical pitch symbols. Below is an example of both:

TAB for guitar actually makes quite a lot of sense (for reasons I’ll explain in a second). Most people imagine tab to be a very recent invention but the concept is actually hundreds of years old, and it evolved at the same time as the development of the first fretted guitar-like instruments such as the lute.

The traditional system of music notation, a.k.a. Standard Notation, works extremely well on piano. However, for several other instruments, there is some degree of difficulty in using standard notation to read and write down ideas.

The guitar is perhaps the instrument that most exemplifies the challenges of classical notation on other instruments. Let me give you a clear example of this:

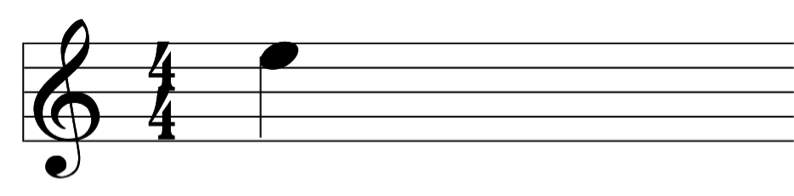

Here is an E note in standard notation:

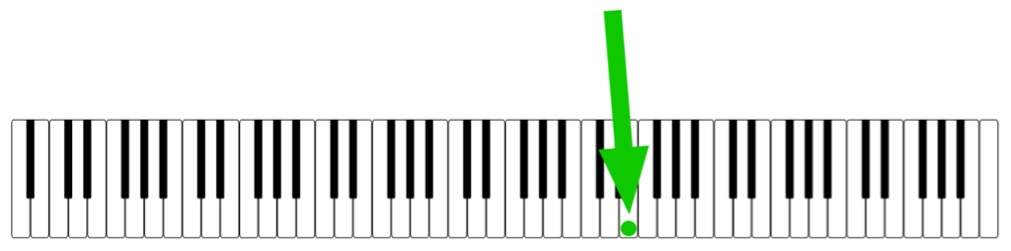

And is where that note would be played on piano:

On piano, so far so good. A specific note in the notation corresponds to one specific key on the keyboard. That makes sense as you’d expect, doesn’t it?

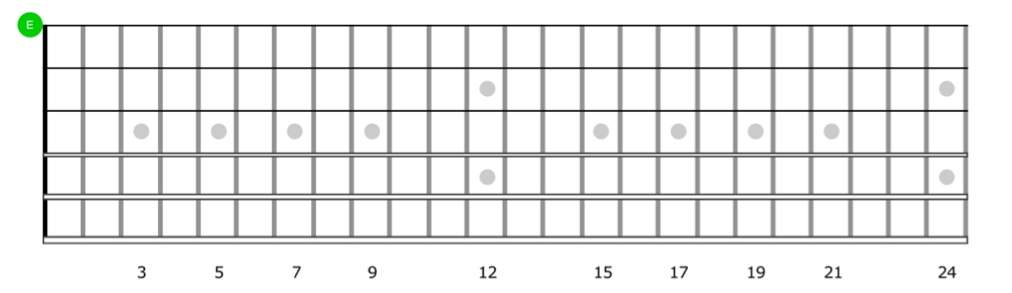

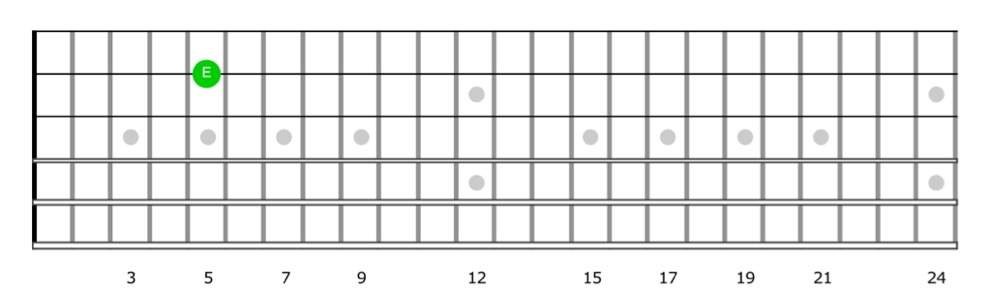

Now here is where the same E note would be played on guitar:

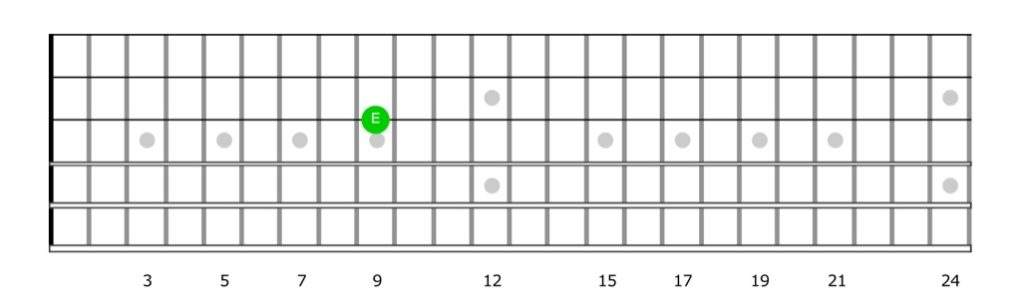

But it could also be played here:

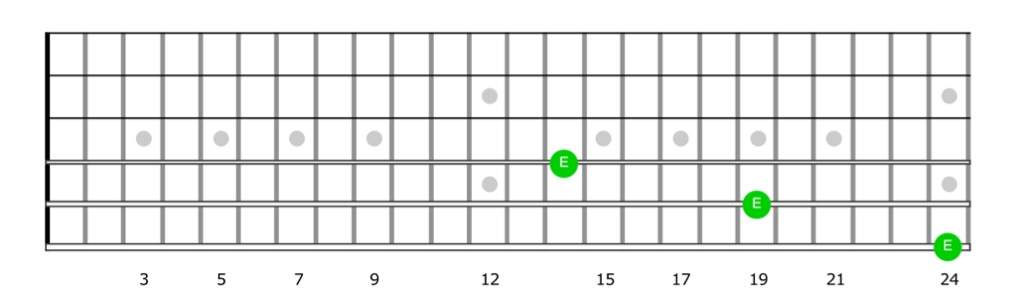

And here:

And also here, here and here:

On guitar we have not one but six places where we could play that note. These aren’t different octaves of E – these are all the same E.

And this is exactly why guitar tab exists – because, on guitar, you can find the same note at the same pitch on several different strings at any given time. This fact makes notation orders of magnitude harder to read for guitar. This is why the majority of guitar players (other than classical guitarists) do not read music, and this is the reason that guitar tab is so popular.

Tab exists for other instruments too, including drums.

The Drums

A standard drum kit consists of 5 main elements or sections – bass drum, snare drum, hi-hat, toms and cymbals. If we break these down further, we typically find:

- Bass Drum

- Snare Drum

- Hihat Cymbals

- High Tom

- Low Tom

- Floor Tom (very low tom)

- Ride Cymbal

- 1 or 2 Crash Cymbals depending on the setup

So there are eight or nine individual items that you can hit on a standard kit. Does that sound like a lot? Let’s quickly compare it to a guitar.

6 string guitar x 22 frets = 132 playable notes

If you have a 24 fret guitar that rises to 144.

And if you happen to play a 7 or even 8 string guitar? You’re looking at 168 to 192 playable frets.

When you have between 130 and almost 200 places you might need to be, that’s a hell of a lot of information to have to keep on top of. So it should be easy to see how tab helps when it comes to guitar.

However, a drum kit has a very small number of “playable pieces” compared to guitar — 8 or 9 versus well over 100 at minimum. In addition to this, there is only one place any particular piece of the kit can be played. If you’re told to hit the snare drum, for example, there can be no confusion what to do because there is only one snare drum in the kit. Unlike guitar, it’s not like you have four or five snare drums scattered around that each have a slightly different tone, and you have to decide within a split second which one to hit.

The point of this isn’t to say that drums are easier to master than guitar. It’s to show that when it comes to reading and writing music, the challenges presented by some instruments are demonstrably greater than others.

With these points in mind, let’s compare a basic beat written in drum tab to the same beat written in notation:

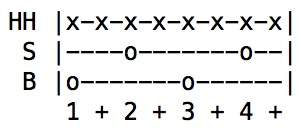

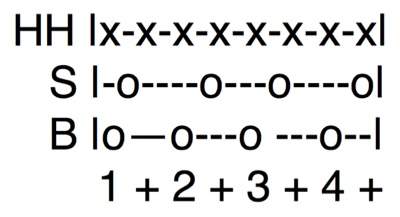

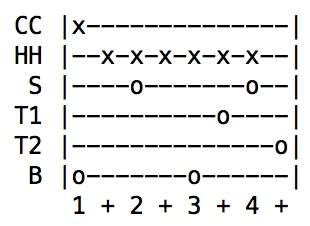

Drum Tab

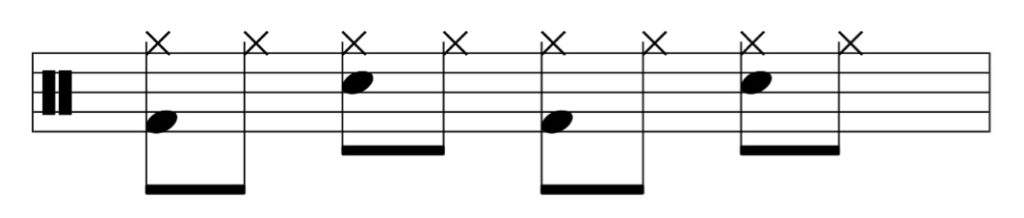

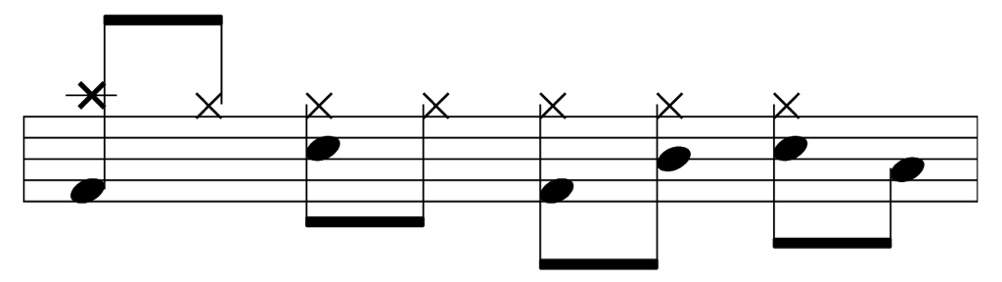

Drum Notation

Both of these display exactly the same rhythm – bass drum on beats 1 and 3, snare on 2 and 4, while the closed hihat plays steady eighth notes on top.

But my question is this:

How does drum tab make things any easier?

It takes no longer to learn that the bass drum is always represented by note heads in the lowest space of the stave (F in the treble clef), as it would to learn that, in tab, it’s the “o’s” on the lowest line marked “B”.

Likewise, it is really no harder to commit to memory that the snare drum is represented by note heads in the second space down from the top (C in the treble clef), than it is to say “It’s the “o’s” on the second line from the bottom marked “S” in tab.

Similarly, what’s the difference between learning to write the hihat as x’s on a line marked “HH”, and just knowing it’s actually the x’s in space above the top line (G in the treble clef) in notation?

There is no significant difference in the difficulty level of reading drum tab or just reading actual drum notation. In fact, I’d say without hesitation that drum tab is ultimately harder to read and certainly to write.

The rhythm above was basically the simplest drum beat we could have, and already the tab looks quite messy. And another thing to bear in mind is that this tab was written in a program that perfectly aligns the columns. Attempt to do it on a standard word processor and your results usually end up looking more like this:

I find that whether it’s well aligned or not, drum tab tends to look like a mess of code.

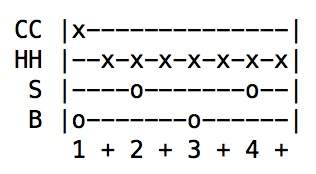

Now let’s say we want to add something to the beat, something simple like a crash cymbal on beat one. Watch what happens:

We have to add a whole new line of tab to the entire score just to mark in one cymbal hit. But here’s how the same thing looks in notation:

The crash cymbal is represented by the dark black X on the first line above the top line (A in the treble clef). It’s nice and clear to see, and it doesn’t add any additional weight to the stave. It’s placement also makes natural sense, because it’s located just up from the hihat. You can look at this and see at a glance that you’re replacing the expected hit on the hihat with a cymbal.

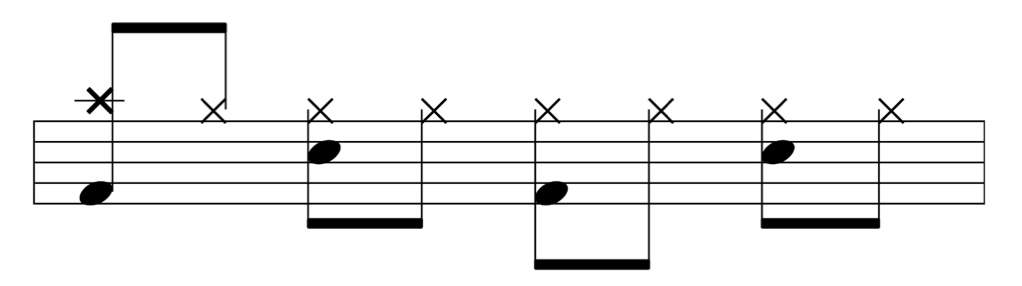

Let’s take one more example, so that I can show you the kind of thing that happens when the beat becomes even just a little bit more complex, with a couple of simple extra elements added:

In tab, this now looks like we’re playing a completely different beat. But all I’ve actually done is add a high tom right before the last snare, and a low tom right after it. I’ve had to add two extra lines (T1 and T2) to the whole thing just to mark these out. Because of where I have to put those lines in tab, the relationship between the bass-snare-bass-snare heartbeat of the rhythm has been obscured.

In notation, the high tom sits just down from the snare drum, on the middle line (B in treble clef), and the low tom sits in the space just below that (A in treble clef). It’s logical because it corresponds to their pitch, and it’s much easier to see how they relate to the other elements of the beat:

Not only is it really no easier to read a drum tab than it is just to read notation, you’re investing your time in getting comfortable with a system that has no musical value and zero transferability. No one, apart from other drummers, knows what drum tab means.

Drum tab is a bit like learning a language that only a few other people speak, when instead you could invest the same amount of time and learn the one everybody is already speaking. Both languages are equally hard (or easy) to speak when it comes to drums, and, unlike guitar, drum tab offers no significant shortcuts or advantages.

The only thing I can think to say in its defence is that in the early days of the internet, bandwidth was at a premium, and a tab written in ASCII computer characters was a much smaller file than a PDF or JPG of written music notation. This made tab files much easier to share around and archive in the past. In this respect, drum tab did a good job of mimicking sheet music well enough to get across what to play.

However the internet of today has no problem handling large documents and images, and a sheet of music is a very small file. Nowadays, when you can download entire scores in an instant, I can’t see any reason at all to be using drum tab.

So, drummers: instead of spending time getting good at reading tab, why not invest a tiny bit more effort and learn how to read and write rhythms as they actually are and as they have been written down for centuries? You definitely won’t regret it.

– Christy